Corona, a new chapter in the story of indoor air quality

During the corona pandemic, a method was developed at VITO for directly detecting viruses like SARS-CoV-2 in an air sample. It is being used in a range of projects to determine the infection risks in indoor spaces where there are many people together. The virus detection method is the next step for VITO in better understanding, predicting and improving indoor air quality – not just for viruses, but also for other pollutants such as chemical substances, moulds and bacteria.

Ventilation systems crucial for air quality

Although the importance of good indoor air quality did not cut through to the general public until the pandemic - with the CO2 meter in classrooms, cafés and restaurants, sports halls and other spaces where many people are close together – the theme has already been on VITO’s agenda for fifteen years. And although a new chapter in the story of indoor air quality has been written with corona, the core message remains about the same: ventilate, ventilate, ventilate. ‘Pollutants are constantly floating around in an indoor space that damage our health and our comfort from certain concentrations,’ says Marianne Stranger from VITO. ‘Whether these are particles of chemical products such as cleaning agents, insulation material or furniture, or biological particles such as bacteria, moulds and of course viruses, it’s about keeping their concentrations as low as possible. You do so in the first instance by limiting the sources (avoiding certain products or at least limiting the quantity used, or for people, limiting the number of people present in a space or having them wear face masks). And next you always ventilate sufficiently, so that the quantity of pollutants in the space drops further.’

Measuring equipment geared to real-world settings

Although the message seems simple, it still often goes wrong as theory and practice can be quite different. The production of pollutants is often dependent on numerous parameters, physical ones like the temperature and air humidity in the indoor space, as well as more behavioural ones such as turning ventilation systems down or off if they are making too much noise, for example. This is particularly the case in spaces where lots of people come together and where there is a lot of ‘walkthrough’ – places like schools, residential care homes, offices. It goes without saying that the lab environment where indoor air experts also do their research may well differ from the real world. And this has consequences for e.g. equipment developed to measure and monitor indoor air quality, or to improve it (by actively purifying the air). But the difference between lab and real world is not insurmountable. ‘Ultimately, I hope to end up somewhere between both settings,’ says Stranger, ‘and to do so by focusing on very specific situations so as to be able to better understand them.’ The brand-new facility that VITO is presently building for testing equipment such as air purifiers (see box below) is also part of the effort to bring lab and real world closer together.

During the lockdown, VITO developed its own method for detecting (among other things) the coronavirus, or SARS-CoV-2, in the air. The method is sensitive and, in addition, can also measure and recognise other viruses. Besides that, it is user-friendly, in the sense that the sampling does not involve any risk of infection (the viral particles are rendered inactive, while their genetic material, necessary for identification through PCR analysis, remains intact). What it roughly amounts to is that the method captures and confines viral particles in a liquid, which can then be taken to a PCR lab risk-free.

A new test lab for air purifiers

Now the importance of good indoor air quality has cut through to the general public and to governments, the next job is to set objective threshold values and standards – not just for indoor air quality, but for equipment for monitoring and improving this as well.

With a brand-new test lab that will be ready in early 2023, and which was designed in accordance with the strictest European standards, VITO is aiming to respond quickly to this too. Stranger: ‘We’ll soon be able to objectively compare air purifiers to one another, for example. But first, we want to determine what an air purifier is actually supposed to do. How much clean air must it produce per hour? There’s no consensus on that at present.’

It is anticipated that the government will shortly issue some new guideline values for indoor air quality in public buildings. The research at the new test lab will contribute to this: among the topics of research will be how these values can be reached and maintained in practice.

Detection method leads to effective interventions against corona

The detection method was and is still being used in various monitoring projects for SARS-CoV-2. For example in the federal government’s AIRCO initiative, which VITO is collaborating on with Sciensano, the impact of ventilation on the presence and spread of the virus in indoor air, as well as on surfaces, is being researched in schools, public transport, sports facilities and residential care homes. The specific characteristics of the indoor space and its use continue to prove decisive. Stranger: ‘With indoor tennis courts, for example, we’ve seen that the risk of infection is very small if a player were to be infected. We had already pretty much demonstrated this in theory during the lockdown, but the practical monitoring is now also showing that.’ A different project emanating from the Flemish government is considering the extent to which ventilation or air purification could be effective intervention measures against corona in real-world scenarios. For the moment, those projects are still focusing on public spaces or spaces where many people come together (such as schools, child day-care centres, catering or sports facilities). But it could well be that the detection method will shortly be used to see the extent to which coaches are corona-proof too, for example.

So the virus detection method is already seeing heavy use, although it could still be somewhat improved. ‘For the moment, for example, it’s still tricky to measure the concentration of viral particles too,’ says Sarah Lima Paralovo from VITO. ‘But we’re working on that at the moment, as the viral concentration will probably help determine the risk of infection, and possibly the seriousness of the infection as well.’

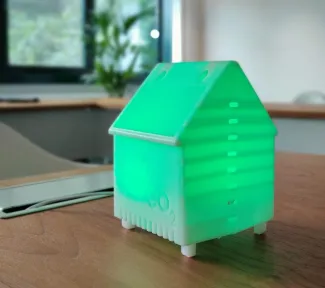

Also during the lockdown, a CO2 meter was developed at VITO that has been put into use across Flanders in a short time. The meter, in the form of a miniature house that lights up green at a sufficiently low CO2 concentration, is very popular in places like schools, which is partly due to the fact that the proper operation of every device is verified by VITO. And although the meter only shows with three colours how well an indoor space is ventilated during the presence of people, this method will continue to play a major role in monitoring indoor air quality. ‘The advantage of a CO2 meter is that it is widely applicable and shows whether there is sufficient ventilation in a simple way,’ says Lima Paralovo. ‘But at the same time, it’s a basic measurement, because if there’s a carpet in the space giving off substances that have a strong smell or irritate the eyes, for example, then the meter won’t tell you that.’ It demonstrates how complex the indoor quality story is.