Prototype digital twin city of Bruges offers opportunities for all of Flanders

In close collaboration, four parties - imec, VITO, Cegeka and the city of Bruges - have spent the past two years building a so-called digital twin of the city of Bruges. This digital representation of the physical living environment, supports policymakers and city makers in taking, monitoring and communicating decisions for their city. Based on historical and current data, they can monitor the condition and evolution of their city, as well as have the impact of their decisions predicted via mathematical models before they are implemented. Currently, this prototype is equipped to map mobility and air quality, as well as their interrelationship.

This blog post was written by imec.

"We are already using the prototype effectively for our day-to-day operations. We are now using the digital twin in several places in our organisation. Firstly, to get a better picture of air quality in our city. And secondly, for supporting policy measures around mobility and their impact on the public domain. Here, we use the digital twin as an additional tool on top of other studies and manual counts. " says Bram De Vreese, data manager at the City of Bruges. "The digital twin currently helps us the most in our communication to citizens. Because we can better substantiate certain mobility decisions, it objectifies dialogues that were otherwise mostly based on assumptions and gut feelings."

Watch the demo video:

Building blocks and functionality

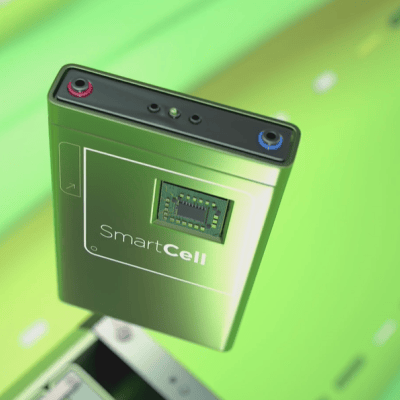

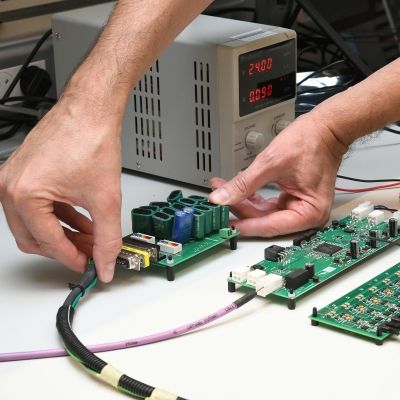

"A whole number of data streams come together in the digital twin," explains Stefan Lefever, technical director at imec. "For mobility, these are data from the sensors of the Agency for Roads and Traffic (AWV), from signalling company SignCO and from the Flemish citizens' initiative Telraam. For air quality, we load in data from the sensors of the Flemish Environment Agency (VMM), from the Bruges startup Qweriu, from the global citizens' initiative Sensor.Community (formerly known as Luftdaten) and from our own measuring bicycle that we have run through the city."

In this way, a whole set of historical and current data in the digital twin become available to the also contributed computational models. For mobility, the consortium relied for this on the model of Cegeka, a Hasselt-based IT company with international experience in rolling out digital business solutions. It won the tender issued by the city of Bruges for this project.

Tim Jacobs, product manager of Cegeka Mobilize explains: "We had already developed our own product based on Artificial Intelligence and big data from our expertise in traffic models outside this trajectory. Still, it was an added value for us to be able to enter this trajectory as a partner and not simply as a supplier. This allowed us to improve our product on a number of points that are specific to historical cities like Bruges. Think of the large numbers of pedestrians and cyclists present in such cities, where our models were typically developed in environments where motorised traffic is dominant anyway. This plays a role when you want to make a 'soft cut' in a street somewhere, for example. Also, the capacity of narrow cobbled roads is less than more recent roads that often fall under the same category on road maps.

Bram De Vreese confirms: "It was very nice for us as a client that Cegeka started working on this as a developer every time we noticed that our measurements in the city deviated from the predicted results from their calculation model. I also notice that the whole project had added value because of the product- and market-oriented approach they brought in as a private party."

In turn, VITO was responsible for the computational modelling of air quality. In the current implementation, the consortium opted for a model that works with annual averages. This gives a good overall picture of the difference in air quality between certain streets and neighbourhoods. It only shows less significant changes in relation to temporary mobility interventions, such as a school street. But provided access to additional data sources, models are also available that map air quality on a more current basis such as by daily or hourly averages.

Stijn Vranckx, researcher at VITO, explains how the project fitted into their agenda: "At VITO, we do broader research into urban living conditions, which also includes issues such as heat stress, land use and flood modelling. Obviously, air quality is also an important parameter and this project was an ideal opportunity to make progress in this respect and make concrete a number of plans that had been on the shelf for some time. For instance, our models were already part of previous digital twin projects, including the European Digital Urban European Twins (DUET) project in which imec was also a partner. Thanks to the project for Bruges, together with imec experts, we were able to link our knowledge in the various domains. It shows that the necessary technical infrastructure can be linked together relatively smoothly once the right context is in place for it."

Interoperability and development process

Nevertheless, a lot of preconditions have to be met for this type of project to succeed. Stefan Lefever calls it an anti-disciplinary approach and explains why digital twins are more than just software development: "A first important aspect in digital twins is societal.

It is essential to show policymakers and city officials how digital twins help make policy decisions underpinned by data: for complex contemporary problems, we no longer let gut feeling guide us. Next is the business aspect. A digital twin requires de facto collaboration between multiple public and private parties. These must therefore be able to exchange data with each other in a scalable, qualitative, reliable and economically fair way.

And then there is the technical aspect. Where you link the necessary data sources and calculation models within the set preconditions so that the right use cases can be addressed. This involves a whole range of aspects such as interoperability, transparency and accuracy. In this, we always try to follow European and other standards, for example as set by the global Open and Agile Smart Cities (OASC) organisation."

Dimitri Schuurman, innovation expert in methodology and monitoring at imec, explains how these aspects recurred in the development process with the city of Bruges: "One of the first important steps was an in-depth five-day innovation sprint in which we mapped, prioritised and elaborated potential use cases using our own developed digital twin use case canvas. We then started a co-creation process with all stakeholders.

Once everything was sufficiently clear, we then started the technical implementation process, which proceeded in three phases: (1) the collection and loading of all data sources, (2) the integration of the computational models separately and (3) aligning them to also explore cross-domain relationships."

Scaling up and next steps

Bram De Vreese followed the entire process as coordinator for the City of Bruges and sees both the advantages and the challenges: "It was an intensive process in which we had to delve more deeply than I had originally estimated. For example, when it came to organising our own sensor data, which we also wanted to bring into the project.

It was also a cultural change to join a development process instead of buying ready-made software. To do that well, the right people had to appear at the table every week, and that did require some internal persuasion at the start. By keeping the end goal and added value in mind at all times, we succeeded and learned a lot as a city organisation.

"Together with cities like Antwerp and Ghent, the city of Bruges is playing a pioneering role in using a digital twin when making policy decisions, but to really deploy it widely in Flanders can also support a regional approach, as is being set up or ongoing in several countries abroad."

Joris Vanderschrick, programme manager sustainable urban environments at imec: "Data-based policy is universal for countries and regions. Although the use cases can change per city or area, I see a great added value in bundling the joint knowledge, developments, products and services and making this optimally available in Flanders, in order to accelerate the broad adoption of digital twins.

In the Netherlands, such an initiative was already worked out at Geonovum, a government foundation (the Dutch equivalent of a vzw) dedicated to data exchange across domains. In it, a vision was elaborated on the realisation of a national digital twin infrastructure for the physical environment, with the aim of sharing knowledge on digital twins. In Luxembourg too, under the leadership of the Luxembourg Institute for Science and Technology (LIST), work is being done on a national digital twin. And in the UK, too, I see a number of initiatives with similar ambitions.

As a country or region, investing in making the necessary solutions available to enable data-driven policies for your citizens and local governments is a strategic choice. And, as far as I am concerned, certainly one that pays off. Flanders has the advantage in this respect that it already has much needed expertise in-house. Looking at our knowledge position regarding digital twins on a European level, I am convinced we can be proud of what we have in house. And also should not miss out on opportunities to benefit our own regional development."