Retaining water in the polders is the new normal

How so, retaining water in the polders? After all, polders are pieces of land reclaimed from the water, and everything there used to revolve around getting rid of it. Yet, since 2017, efforts in this drained polder landscape have also been directed at retaining water instead of only discharging it. This has led to dynamic water and level management—but what does that actually mean?

We set up the entire polder system with dikes, drainage channels and pumps in order to drain the land so it could be cultivated: grazing meadows, potatoes, silage maize, beets and all kinds of vegetables. In the meantime, characteristic nature has also developed, such as creek landscapes and areas where meadow birds can breed. In this human-made landscape, we can enjoy the wide horizons, the ditches, creeks and rows of trees. It is also part of the identity of those who live there.

You could therefore see humans as a (hyper)keystone species in the polders. Without humans there would be no polders, no polder agriculture, and not even the current types of nature that we value there. Although there are sometimes conflicting interests between nature managers and farmers, they are connected through water management in the polders.

That water management is carried out by the polder boards, the Flemish Environment Agency (VMM), the provinces and De Vlaamse Waterweg. For centuries, they have worked hard with all the water managers to devise and implement a system to drain excess water from these areas.

A keystone species is a species whose impact on an ecosystem or community is greater than would be expected based on its abundance. Such a species plays a pivotal role: if it disappears, the entire system changes. If humans were not present, the whole polder farming system with its current nature types would largely disappear.

Examples of other potential hyper-keystone species include the reintroduced wolves of Yellowstone, and even the pre-Columbian populations who helped shape the Amazon rainforest by enriching the soil with carbon (terra preta) and spreading useful plants.

Or the Indigenous communities of the North American plains, who shaped that landscape through their way of life. We are therefore undeniably part of nature.

A bit of polder history

The same goes for the East and West Flanders polders along the Dutch border. They, too, have been around for centuries and were not only battered by the weather gods, but also by territorial divisions. When we in Belgium showed the Northern Netherlands with their authoritarian king the door in 1830, he (after nine years of stalling to give up part of his territory) shut the door on our polder drainage through what is now Zeeland. “Let those annoying Belgians get wet feet then,” he must have thought. Because now the Belgian polders could no longer get rid of their water and they became breeding grounds for malaria mosquitoes, leading to so-called “polder fever.”

And so our ancestors sought a solution to drain the polder water via a channel to the North Sea at Heist. In twelve years’ time, the 46-kilometer Leopold Canal was dug by hand (with shovels) between Heist and Boekhoute (Assenede) to relieve the need via this “Blinker.” The original plan, which would have extended the canal to the Ghent–Terneuzen Canal, ultimately didn’t need to be fully implemented. That’s how it often goes with long-term infrastructure projects: they are subject to changing circumstances. Just ask Antoni Gaudí or the Antwerp city council.

And what had changed? After a few years of digging, there was already less animosity between the Belgians and their northern neighbors, and a few decades later they were able to get along somewhat better. This led to the construction of the Isabellakanaal, which on the eastern side of the polders provided drainage through the Netherlands.

Kantelstuw in het grensgebied met een Nederlandse én een Vlaamse peilmeter

The WIJ-Water Project – adapting the polder system to climate change

The historical sketch above shows how we have dealt with changing circumstances in the past, and how our landscape and its functioning are the result of choices we as a society made—based on our needs at the time and against the backdrop of our knowledge of the environment and climate. The polder system has always been aimed at draining excess water, and the Leopold Canal and the Isabellakanaal are living proof of this.

The West and East Flanders polders along the Dutch border depend on these two canals—either through pumping or simple gravity drainage (when the ebb tide of the North Sea allows it), siphons under canals, adjustable or fixed weirs, and waterways with inlets and outlets. It is a complex system that directs all the water from the various parcels, separated by ditches, through those major canals to the sea.

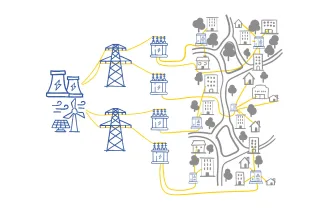

It is a tangled network that nearly rivals the complexity of our electricity grid—though it works the other way around. The electricity system used to have just one goal: bringing electricity from large power stations to every household. From central to decentralized. The polder system, however, works in reverse: from decentralized parcels, via ditches, to the central drainage canals (see figures 1 and 2).

Figuur 1: van centraal naar decentraal - het energienetwerk (van het verleden)

Figuur 2: van decentraal naar centraal - het waternetwerk (van het verleden)

But what if it gets drier, and in the meantime we could make sweet deals (or croquettes) with Willem from the Water Board in Zeeland? To continue the parallel above: what if electricity suddenly flows into the grid via rooftops with solar panels and all sorts of other small-scale “mini-decentralised units”? Then the system must change—or we’ll face congestion.

The times they are a-changin’, or, as transition and sustainability expert Jan Rotmans paraphrasing Bob Dylan reminded us: “We are not living in an era of change, but in a change of era.”

The same applies to the polder system. It has to be adapted. Is it still “of this time” to simply send all that precious water to the sea? Can we keep it longer in those drying plots when it doesn’t rain for months? Can the canals help as large water reservoirs? And is that water of sufficient quality? So many questions, so many uncertainties.

To answer the above questions and to set a number of actions in motion, various water managers together with research partners across borders are carrying out the WIJ-Water project. The Province of West Flanders, the Flemish Environment Agency (VMM) and De Vlaamse Waterweg, which manage the waterways, along with the Oostkustpolder, Middenkustpolder and Polder van Maldegem, and the Zeeland Water Board Scheldestromen are working together with Sumaqua, HOGENT, HAEDES and VITO to explore how we can make this system transition, together with all other actors in the landscape.

This system transition aims to use not only water bodies, but also the soil as a freshwater battery to counteract drought and salinisation during major rainfall shortages. At the same time, the system must still be able to drain away excess water quickly (or even faster than before) when necessary, because climate change of course brings us not only long dry periods but also intense local downpours.

WIJ-Water in practice: learning through experimentation

We prefer not only to ask questions, but also to try to answer them. That is why experiments are already underway—because in times of uncertainty, experimenting is an important strategy.

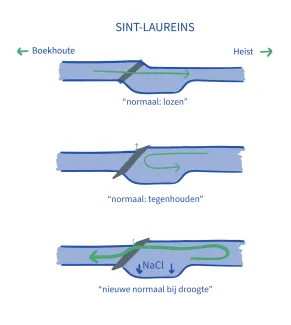

On the Leopold Canal, near Sint-Laureins, there is a weir that serves to drain water from the eastern polders toward the sea in the west. At the same time, this weir prevents salt or brackish water (of lower quality) from the western section from flowing eastward toward the inland. For that reason, under normal circumstances the weir is set so that water can always flow from east to west toward the sea, but never the other way around. In normal conditions (as we were used to until just a few years ago), the canal discharged fully into the North Sea. When there is too much inland rainfall and therefore water levels in the eastern part of the Leopold Canal become too high, not all the water can pass this weir to the sea. The excess water can then be pumped additionally at Boekhoute into the Isabellakanaal toward the Netherlands and further north into the Western Scheldt.

In recent years, under the new normal conditions, this weir has been used differently during drought than it was originally designed for. In periods of prolonged drought, the water managers decide together not to simply let the water flow away to the sea, and thus to reduce or even stop discharges at Heist—because once that water is gone, it is irretrievably lost. The water still arriving from the polders into the western section of the Leopold Canal then begins to accumulate over a stretch of 27 km. Water levels in the western section rise and become higher than in the eastern section. Since it cannot drain via Heist, it begins to flow back eastward. The weir at Sint-Laureins, whose normal function is to discharge from east to west, must still prevent the brackish and saltier water from the western part of the canal from flowing into the eastern part. (See Figure 3). The question is: how can this weir still fulfill its function under these new normal conditions?

Figuur 3: omgekeerde werking van de stuw in Sint-Laureins

A characteristic of saltwater is that it is heavier than freshwater. Freshwater, as it were, floats on top of saltwater. For this reason, experiments are being carried out to reverse the operation of the weir during periods of drought and allow a thin top layer of freshwater from the western section of the Leopold Canal to flow back over the weir toward the inland.

Because the weir is single-acting, it must be pushed below water level with the help of a crane. In this way, during drought, freshwater flows over the weir inland and keeps water levels in the East and West Flanders polders stable. By maintaining higher levels in the Leopold Canal and the polders, freshwater even flows via Boekhoute into the Dutch polders. So we also save the Dutch from getting too dry feet. One wonders: what would King Willem have said about that?

Such experimentation and inventiveness are important, but we also need to arrive at structural solutions that take an uncertain future into account. This is what WIJ-Water will continue to work on for several more years, so that we are better prepared in the long term for the change already underway and the change yet to come.

At the Flemish Environment Agency (VMM), which manages the weir, consideration is already being given to eventually making this weir double-acting, so that no makeshift adjustments with a crane will be needed to retain as much water as possible in the fight against drought and salinisation.

Manipulatie van de stuw in Sint-Laureins zodat zoetwater van west naar oost kan stromen.

Change – difficult, but the only constant

We have shaped our own landscape, and the entire polder system bears witness to that. Within this lies the potential to reinvent the landscape and to transform the systems. In doing so, we can take up our role as a hyper-keystone species in tackling climate change.

Climate adaptation grounded in a regenerative approach requires us to look far enough ahead, to think outside the box, free from taboos, with a focus on the potential of the landscape and its actors, rather than starting from a problem-oriented perspective. It calls for an approach that respects everyone’s perspective and creates space to reinvent ourselves in times of great change. This is what we are working on together with WIJ-Water. Because standing still means … drying out.

♫ “And you better start swimmin’

Or you’ll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin’” – ♫

(Bob Dylan)

With thanks to Interreg Flanders–Netherlands, Province of West Flanders and Department of Environment.