Without the Building Shift, a massive amount of open space will be lost

Flanders must be very careful with its open space. That's why the Flemish government has set the basic principle of space neutrality as part of its spatial policy, with the aim of achieving this by 2040, also known as the Bouwshift (Building Shift). By 2040, it wants to reduce the daily intake of open space to zero hectares. After that, new construction can only take place in areas where buildings already exist. HOGENT and VITO have investigated how open space has been taken up over the past 50 years, the role of regional planning in this, and how this can further evolve in the future. One thing is clear: without the Building Shift, Flanders risks losing more than 40,000 hectares of nature and agricultural land.

The first digital version of the zoning maps was only introduced in 1994. However, there were preliminary designs for 25 regional plans covering the whole of Flanders since the late 1960s. The historical study shows that the "cluttered" Flanders, as we know it today and which involves significant social costs, has already emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. As the preliminary regional plans evolved into their final form, more and more built-up plots, which were scattered or in ribbon development, were designated for housing. If the space reserved for construction was already ample, it became even larger. This oversupply was justified on the basis of economic reasons such as the fact that "available space for economic activity creates more economic activity". Budgetary reasons were also cited. For example, it was claimed that building land would remain affordable. Governments also argued that citizens should have the choice to live where they want and that they had the right to choose a rural lifestyle. Behind all of this was mainly the fear of damage claims and the resulting compensation by (land)owners.

To this day, these 43-year-old regional plans continue to largely determine spatial planning for much of Flanders. Since the finalisation of the regional plans, only 5% of the Flemish territory has been changed as a main destination (1980-2020). Thus, very little changes (or improves) regarding these old zoning plans, despite changing societal and ecological circumstances.

Nature and Agriculture Filled with Unplanned Space Consumption

What this study has also shown is that a large part of the additional land use - about one third - was allowed in an 'unplanned' manner in soft destinations such as agriculture and nature. This was not provided for in the urban planning regulations. The regional plans did not bring about any adjustment to keep developments more together in designated zones. The figures show that the 'unplanned' share of land use in soft destinations is even increasing in recent years due to the exception culture of non-compliant zoning rules. As a result, more than 50% of the land use ends up in soft destinations. The additional land use (1975-2020) is 'spread out' over the country and shows hardly any compactness or concentration, except for the developments of seaports, the national airport and some industrial estates in Limburg. Moreover, the speed of spatial consumption during this period was 2.5 times faster than population growth.

What if the construction shift is actually implemented

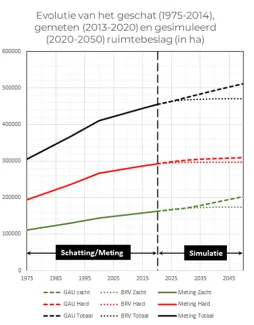

The study also examined how land use in Flanders could develop until 2050. Where and how much land use will increase if policies are not changed and we assume that land use continues at the same rate as measured in the last decade (scenario growth-as-usual, GAU, or 5 ha/day of land consumption). And, how does this differ with the implementation of new policies, namely the application of densification and protection principles from the Spatial Policy Plan Flanders (scenario BRV)?

The results are remarkable:

- The excess supply of hard destinations created in the 1960s and 1970s remains present in both scenarios. Projections show that a large part of these hard destinations will not be affected. This is mainly due to the poor location of a large part of the remaining building land in relation to demographic and economic needs and projections. The researchers therefore conclude that the excess supply of (poorly located) land can be neutralized or repurposed without affecting development opportunities for Flanders. This can be achieved with only a limited densification (+6%) of existing residential areas. This conclusion confirms the results of another recent study that examined future housing needs in Flanders and found that there is a significant excess of residential areas compared to future housing needs.

- The difference that the "Bouwshift" (Building Shift) can make for open space is significant, as the comparison of the two scenarios clearly shows:

Additional land use 2020-2050 in Flanders, in growth as usual scenario (above) and in implementation of policy scenario BRV (below)

New in this study is the finding that taking no action (GAU) will lead to a further loss of about 29,000 hectares of open space in soft destinations and 13,000 hectares in hard destinations by 2050, compared to a scenario where the policy plan (BRV) is put into effect. The Bouwshift can provide the greatest differences and spatial gains, especially for the open space destinations of agricultural and green zones.

More protection of agricultural and natural spaces is needed, especially in the central part of Flanders which is under the most pressure. Two policy tracks offer perspectives if we want to preserve open space: the limitation of expansion opportunities for zone-exempt buildings and conversions of agricultural land on one hand, and on the other hand, neutralizing/re-purposing a portion of hard destinations.

The overall picture of the historical evolution of spatial use in Flanders and what the future may hold with (no) policy changes is shown in the graph below.

Evolution of land use in Flanders in hard destinations (red) and soft destinations (green), from 1975 to 2020, and projection from 2020 to 2050 with trend and implementation of new policy.